Ocean Acidification (OA) – Part I

Today I’m posting about what to me is some recent environmental research of the unnerving sort. Ocean Acidification – global warming’s “equally evil twin.” I’ve lately been reading New Yorker Science writer Elizabeth Kolbert’s “The Sixth Extinction,” published last year by Henry Holt and Co.

In the chapter “The Sea Around Us,” Kolbert offers a case study of ocean warming and its ramifications at Castello Aragonese, a small island rising, as she says, “straight out of the Tyrrhenian Sea” and connected by a stone causeway (built 1438) to the Italian coast 18 miles west of Naples. In large measure, it’s a tourist site these days.

In the chapter “The Sea Around Us,” Kolbert offers a case study of ocean warming and its ramifications at Castello Aragonese, a small island rising, as she says, “straight out of the Tyrrhenian Sea” and connected by a stone causeway (built 1438) to the Italian coast 18 miles west of Naples. In large measure, it’s a tourist site these days.

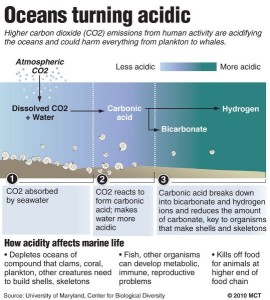

Permit me some background. As you know, the oceans cover about 70% of the earth’s surface. Wherever water and air come into contact, gases from the atmosphere are absorbed by the ocean and gases dissolved in the ocean are released into the atmosphere. With me so far? Ok.

When these exchanges are in approximate equilibrium, the pH of the oceans’ surface waters leaves us with the kind of marine life known in the current era. But, when in disequilibrium due to human-created CO2 in the atmosphere increasing by as much as a couple of billion tons annually in the recent 2 years, the pH of the oceans’ surface waters has dropped, according to Kolbert, from an average of about 8.2 to an average about 8.1.

Doesn’t sound like much ’til you realize this change is on an order of magnitude similar to the Richter scale, i.e., 0.1 change equals a real lot. According to Kolbert (who may have gotten it from NOAA), this magnitude of decline represents 30% more acidification than at the start of the Industrial Revolution (late 1700s). By the end of the century, scientists are predicting that the average oceanic pH level will drop to 7.8. As Kolbert notes, that translates to a level 150% higher than the same late 1700s. According to NOAA, this high a level of acidication hasn’t been seen for 20 million years. (If you think this might be a typo, look here.)

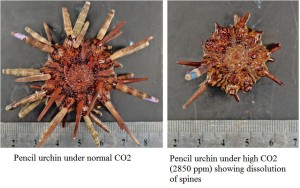

Due to tectonic plate shifting, ocean floor “vents” ring a portion of Castello Aragonese. From these vents comes gas that’s nearly 100% CO2. Marine life around these vents show the effects of substantially higher pH, or acidification. While a band of whitish barnacles mostly rims the island, above the vents there are no barnacles. Sea urchins and mussels are absent from this area too. Scientists known to Kolbert have captured animals from areas near these vents for critical examination of what effect there may be from lower pH levels.

“There is a starfish missing a leg, and a lump of rather rangy-looking coral, and some sea urchins, which [normally] move around on dozens of threadlike ‘tube feet’ but here show next to no feet. “There is also a six-inch-long sea cucumber, which bears an unfortunate resemblance to a blood sausage, or worse yet, a turd.” The life of these marine animals has been damaged. In another example, a common, healthy Mediterranean snail has a shell of alternating black and white splotches, snake-like in pattern. Those taken from near the Castello Aragonese vents have no pattern and the ridged outer layer of the shells have been eaten away.

“There is a starfish missing a leg, and a lump of rather rangy-looking coral, and some sea urchins, which [normally] move around on dozens of threadlike ‘tube feet’ but here show next to no feet. “There is also a six-inch-long sea cucumber, which bears an unfortunate resemblance to a blood sausage, or worse yet, a turd.” The life of these marine animals has been damaged. In another example, a common, healthy Mediterranean snail has a shell of alternating black and white splotches, snake-like in pattern. Those taken from near the Castello Aragonese vents have no pattern and the ridged outer layer of the shells have been eaten away.

Another effect of lower pH levels is that oceans will become “noisier.”

What of all this? Read the book for more. Meanwhile, Kolbert offers that scientists claim ocean acidification at the forecasted level has played a role in a least 2 of “the Big Five extinctions” of the past. Occurring about 250 million years ago, the end-Permian extinction caused up to 96% of all marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species to become extinct. Kolbert says that ocean acidification in our time will alter the makeup of microbial communities, such as the key nutrients of iron and nitrogen. It will also promote toxic algae growth and, due to change in the amount of light passing through the water, impact photosynthesis too.

So, higher loads of GHG emissions from human activity not only has the effect of global warming, such as sea rise and abnormal temperatures already experienced (Super Storm Sandy and the bone dry climate of the Southwestern U.S.), but marine life as we know it appears on an accelerated path of imbalance and uncertain change.

Part II of this post will describe the effects of ocean acidification on coral at the Great Barrier Reef.