Water & Subsidence, Part 2 – Hampton Roads and Norfolk Naval Station

Setting on the nation’s largest know geological impact crater, the Hampton Roads area is sinking at an average rate of 4mm/yr. Sea rise, along with subsidence, is creating a planning challenge for the Navy Department as well as city and regional officials.

Setting on the nation’s largest know geological impact crater, the Hampton Roads area is sinking at an average rate of 4mm/yr. Sea rise, along with subsidence, is creating a planning challenge for the Navy Department as well as city and regional officials.

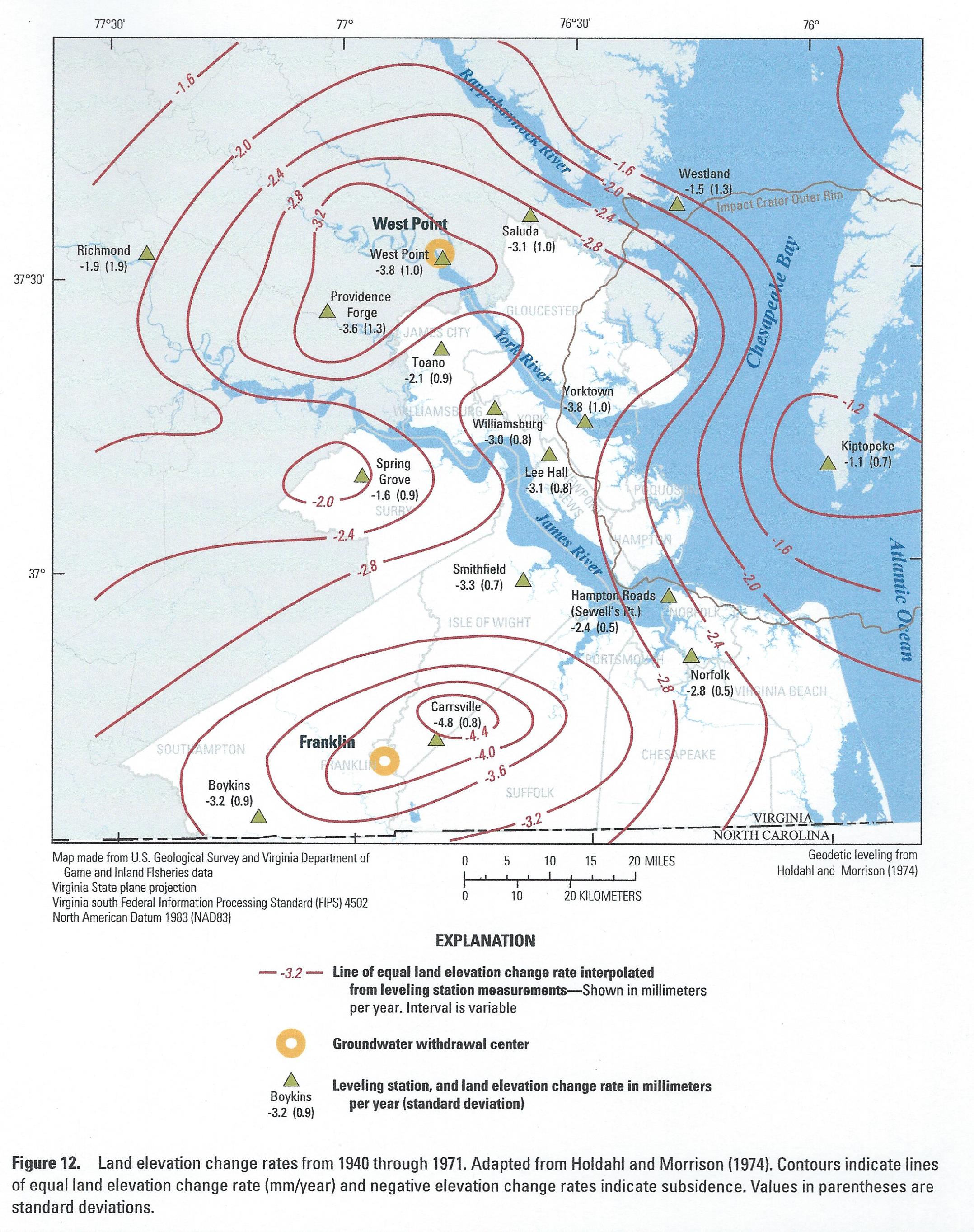

As stated in the 2015 Re.invest Initiative City Report – Norfolk: “About 10 to 12% of Norfolk is underlain by filled wetlands and former submerged areas. Its coastal location at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay means that it also has to contend with projected sea level rise. According to the USGS [2013] land subsidence has been observed in this region of the Chesapeake since the 1940s at rates between 1.1 to 4.8 millimeters per year. Land subsidence coupled with projected and recorded sea level rise increases flooding risk within the City of Norfolk.”

In the Hydrology section of the report: “The low lying nature of the city’s location coupled with heavy rains, the susceptibility to storm surges and the presence of storm water discharges from a large upstream contributory watershed makes Norfolk subject to frequent annual flooding. Where precipitation flooding coincides with tidal flooding and storm surge the existing storm drain infrastructure is incapable of conveying runoff downstream; this exacerbates flooding. Stacking tides, or high tides that accumulate over several cycles coupled with precipitation flooding, can cause more flooding than a hurricane.”

For Norfolk waterfront communities, one proposed solution: “The installation of a self-raising flood barrier along the waterfront area can potentially eliminate this problem. Initially developed in the Netherlands, this solution has been deployed in the Netherlands, Belgium, the United Kingdom, and most recently in a small scale outside of the National Archives in Washington, DC. This passive flood defense system, through hydraulic principles, uses the rising floodwater to automatically raise the flood barrier. As the floodwaters recede the barrier automatically retracts. The beauty of this system lies in the fact that it is virtually invisible allowing residents to keep their unobstructed waterfront views when not in use and does not require human intervention or a regular power source for deployment.”

For Norfolk waterfront communities, one proposed solution: “The installation of a self-raising flood barrier along the waterfront area can potentially eliminate this problem. Initially developed in the Netherlands, this solution has been deployed in the Netherlands, Belgium, the United Kingdom, and most recently in a small scale outside of the National Archives in Washington, DC. This passive flood defense system, through hydraulic principles, uses the rising floodwater to automatically raise the flood barrier. As the floodwaters recede the barrier automatically retracts. The beauty of this system lies in the fact that it is virtually invisible allowing residents to keep their unobstructed waterfront views when not in use and does not require human intervention or a regular power source for deployment.”

Heard of vegetated “green roofs”? How ’bout blue roofs? (I hadn’t.) The Report states: “Blue roofs are non-vegetated point source controls that detain stormwater in much the same way as green roofs but without the ecological benefits. Blue roofs also have the added benefit of reducing the urban heat island effect and are generally less costly to install and maintain than the more widely known green roof. Modular gravel filled watertight trays (open to the atmosphere) allow water to pond temporarily until the water attains the height of the tray and overflows and drains off the roof at the existing roof drains. Since roof waterproofing is essential, older building may need to have roofs upgraded or repaired before installation of the blue roof system. Structural concerns due to the weight of water are less of an issue as buildings in Virginia are built to accommodate snow loads and this load would be similar to the anticipated 15-20 pounds per square foot anticipated loading on a blue roof from the weight of gravel, other materials and water.” Imagining lots of building owners opting for retaining water on rooftops is a stretch, IMO. If financially incentivized for risks…?

Another means of deferring flooding is the use of Green Street technology, the so-called stormwater tree trench.

These means, and others described in the report, become an integrated flood management system for Norfolk, and potentially other coastal urban areas such as Baltimore City and New York City. How to pay for it? Special assessment tax districts is one means. Public-private ventures (PPVs) and other kinds of partnerships are possible.

So, where’s the Navy in all of this? Headed underwater is the short answer. A Virginian-Pilot article of November 2, 2013 says this after the results of a 3-year Army Corps of Engineers study were released: “Norfolk Naval Station’s vital infrastructure wouldn’t survive the kind of powerful storms and widescale flooding that rising seawaters are expected to bring by the second half of the century. And those conditions would likely get even worse in the following decades.”

So, where’s the Navy in all of this? Headed underwater is the short answer. A Virginian-Pilot article of November 2, 2013 says this after the results of a 3-year Army Corps of Engineers study were released: “Norfolk Naval Station’s vital infrastructure wouldn’t survive the kind of powerful storms and widescale flooding that rising seawaters are expected to bring by the second half of the century. And those conditions would likely get even worse in the following decades.”

“For example, since 2001, the Navy has been building expensive double-deck piers in Norfolk that are supposed to last for decades. They protect the utilities on the lower decks from water damage – based on current sea levels. That works now, [one of the report’s authors] said, but because they weren’t designed to address climate change, they won’t be usable as long as expected.” These piers, at the upper deck, are 21 ft. above sea level.

“The results found that at some point between a 1.5-foot and 3-foot rise of the sea, the Navy base – and much of Hampton Roads – would be submerged for hours or even days by a big storm. Without proper planning, the base would be unable to function.” Retired ADM David Titley, the former oceanographer of the Navy, said that based on NOAH’s prediction that sea level will rise from 1.5 feet to more than 6 feet by 2100 the Navy should plan for 3 ft. and respond accordingly. (lol)